Trans-disciplinary Marine Sciences: Beneath the tip of the iceberg

In my graduate studies, I embarked on a journey to study Arctic marine ecosystems and fisheries in ways that collaborate with and bring together different ways of knowing. Now as a postdoc, I’ve continued on this path of constant learning; a path of transdisciplinarity that, though more and more encouraged and supported in academia, is still considered ‘outside the box’ and atypical. Taking this path in my journey has been deeply enriching and transformative, but it hasn’t come without challenges: a typical experience for early career researchers (ECR) and early career ocean professionals (ECOP) that are pushing forward community-collaborative research, and whose status involves more insecurity (professional, financial, etc.; e.g. MacMillan, Falardeau, et al. 2019). Navigating transdisciplinarity as an early career researcher requires a willingness to self-reflect and learn every day, a great deal of flexibility, as well as faith, perseverance, and patience.

For example, this spring, a critical part of my doctoral thesis was published, after a long-term process spanning… seven years! The backbone of this chapter studied the High Arctic marine ecosystem and Arctic Char fisheries, using mixed methods that brought together insights from Inuit fishers’ knowledge and Western science. Throughout the project, I had to keep faith that embracing a transdisciplinary approach and prioritising relevant outputs to the community was the right thing to do. Even if it meant publishing much later in my PhD journey, in a work environment where publications are still a critical currency of productivity and measure of success.

In this kind of research, a paper is the tip of an iceberg that is formed of a much deeper community-collaborative process.

However, in community-collaborative research, each step of the process has a different pace, from developing the research design to disseminating the results in a bottom-up fashion (starting with local communities, ending with the academic audience), and publishing. The outputs are also of different nature, ranging from using films (like Hivunikhavut that I made at the end of my PhD) and other art forms that are not typically recognized in grad studies and other academic evaluations (but, this is changing!).

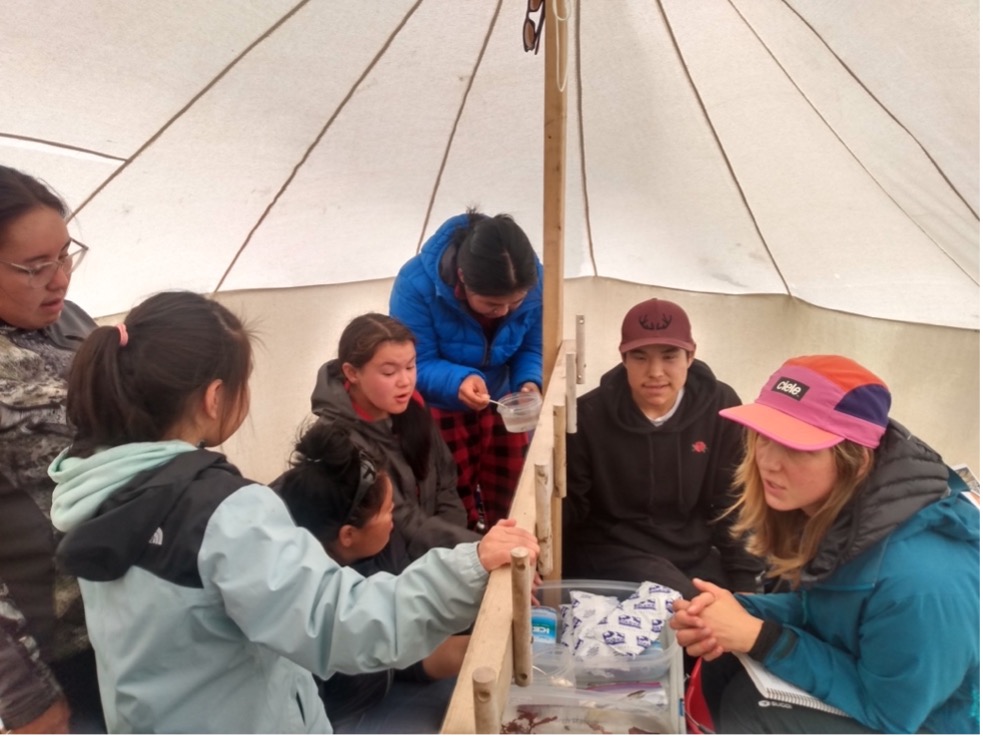

From the outside, it can look like a lengthy, slow, process, but the work never stops, trust me. Each step of the way, I had to persevere in my efforts to push forward the ‘invisible’ aspects of transdisciplinary research, such as building trust and connecting with community members for their guidance, input, and feedback, attending community gatherings and meetings, organizing participatory activities, producing outputs that could resonate with community members, disseminating first the research to the community and checking in for feedback. Ultimately, we completed a paper with a fantastic team of co-authors from multiple disciplines. But in this kind of research, a paper is the tip of an iceberg that is formed of a much deeper community-collaborative process.

“Navigating transdisciplinarity as an early career researcher requires a willingness to self-reflect and learn every day, a great deal of flexibility, as well as faith, perseverance, and patience.”

Learning from the Experts on the Land

Our publication was the project’s conclusion, revealing important shifts in the High Arctic’s marine ecosystem and Arctic Char fisheries, as well as the unique combination of approaches that allowed us to study these changes. Combining different pieces of information from Inuit fishers’ knowledge to biophysical indicators formed a cohesive picture of environmental changes over the past few decades.

For instance, Western science techniques (e.g. using stables isotopes and morphometric measurements in fish) served to measure shifts in Arctic Char diet and condition, while Indigenous Knowledge revealed a suite of changes that not only connected to findings observed by Western science, but went well beyond what that lens can observe. Inuit harvesters are full time on the Land; they are the absolute experts of the ocean. They observe subtle yet critical changes reshaping it, such as increasing observations of boreal forage fish (in the environment and in animals’ stomachs), or the influence of higher shore water temperatures on fish behaviours. Critically reflecting on this multiyear process, we identified ways forward for improving how we do collaborative research at this interface, and I’m excited to build upon this experience as part of my current research in Inuit Nunangat.

Legend: Graphical abstract of recently published paper ‘Biophysical indicators and Indigenous and Local Knowledge reveal climatic and ecological shifts with implications for Arctic Char fisheries’.

Continuing the Journey

Continuing on my path as a transdisciplinary marine scientist, most of my energy since I started my postdoc has been directed toward community consultations and collaborations, spending over four months in northern Indigenous communities to set the stage for meaningful community-based research. Again, in terms of typical academic outputs, the footprint may not be obvious, but if you put on transdisciplinary lenses, you’ll see how far underwater the iceberg goes.

About the Author

Marianne Falardeau is a postdoctoral researcher (Université Laval, Quebec City) who holds a Ph.D. in Natural Resource Sciences (McGill University, Montreal), as well as a B.Sc. and an M.Sc. in Biology (Université Laval). She studies marine ecosystems in the context of climate change in the Arctic, and the importance of marine resources, especially Arctic Char fisheries, for food security and health in coastal Indigenous communities. Her research seeks to guide conservation and sustainable management in the Arctic. Marianne’s approach to research brings together different types of knowledge, including Indigenous and Local knowledges. Marianne is also an eager science communicator who shares her research through articles, conferences, short films, interactive workshops, and new media.